Prague was the fourth stop of the trip: a marvelous and culturally rich city, with a peculiar story regarding war(s). Crossed by the Vlatva, it is known by its magnificent city center that depicts very coherently all the periods the city went through. From being the official residence of several Holy Roman Emperors, to witnessing the first signs of the Reformation and being a bubbly cultural hub in the late 19th century, the city has a vast number of heritage sites worth a visit.

[A view of Prague and of the Vlatva]

* DURING WWII *

As WWII was beginning, Prague was the capital and major city of Czechoslovakia, a republic formed in 1918 that used to unite the modern day Czech Republic and Slovakia. Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia started even before the beginning of the war. In 1938, with the signing of the Munich Pact, a compromise between Germany and England, Sudetenland, a bordering region with strong affiliations to german culture, was annexed, in the hopes it would satisfy Nazis’ expansion intentions. However, in March of the following year, the rest of the country was occupied as well, as Hitler only gave two options to the at that time president Emil Hácha – occupation or total destruction.

The capital of the Bohemia and Moravia Protectorate – as Nazis called it – lived years under terror during the full duration of the conflict. Even thought it was mainly spared of mass destruction due to shelling, as it was only bombed once by the end of the confrontations – and by accident! -, Prague witnessed profound transformations and the loss of important heritage sites, specially after 1941, under the rule of Reinhard Heydrich, also known as the Butcher of Prague.

The Jewish Quarter was tremendously altered with the creation of one of the biggest ghettos created during WWII and the old town severely damaged as a consequence of the Prague Uprising, an attempt to liberate the city from the Nazis, only a couple of days before the cease of the conflict in Europe.

[The main square in the Old Town of Prague, classified by the UNESCO since 1992, and its famous Astronomical Clock]

* WORLD HERITAGE 101 *

The Historic Centre of Prague was inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1992 and it is a great example of urban coherence and quality, combining harmoniously medieval structures, baroque churches and Art Nouveau buildings. Nowadays, Prague is a city visited by copious amounts of visitors, having to cope with the challenges brought by mass tourism, but at the same time, it seems to have been able so far to keep an uniqueness that provokes amazement in each single neighborhood.

* JOURNAL *

DAY 6: The City Centre

My first day in the Czech capital started with a walk through the old town – Stare Mesto – the medieval settlement from where the city later expanded. Starting at the main square, I admired the Old City Hall building, where the symbol of Prague – the Astronomical Clock – lies. It was heavily damaged by the Nazis as a retaliation for the uprisers at the end of the conflict and it took a couple of years to be repaired. However, and even though several architectural competitions were held in the following decades, the plot where the damaged part of the building layed remains empty and the wall that faces the square, clearly cut, speaks of that disruption and that event in czech history.

[The main square in Prague / The Old City Hall, partially destroyed during the Prague Uprising, that was never rebuilt]

Walking through the organic medieval street network in direction to the river, there was still time to visit the Rudolfinum, the building where Dvórak premiered his famous “Slavonic Dances” and that nowadays hosts the Czech Philharmonic. It is a prime example of the not-so-obvious destruction that WWII left on the city: as a strategical point for Nazis, Prague and its buildings were often occupied by passing troops that used major architectural landmarks of the city in a way that often didn’t respect its richness, massively altering and altering its interiors. The Rudolfinum, for instance, was an entertainment hall for Nazis, where they would recreate plays and concerts inside to create entertainment and raise the spirits of high ranked German officers, while war was erasing Europe.

[The Rudolfinum, now house to the Czech Philharmonic]

DAY 7: Bombed by Mistake

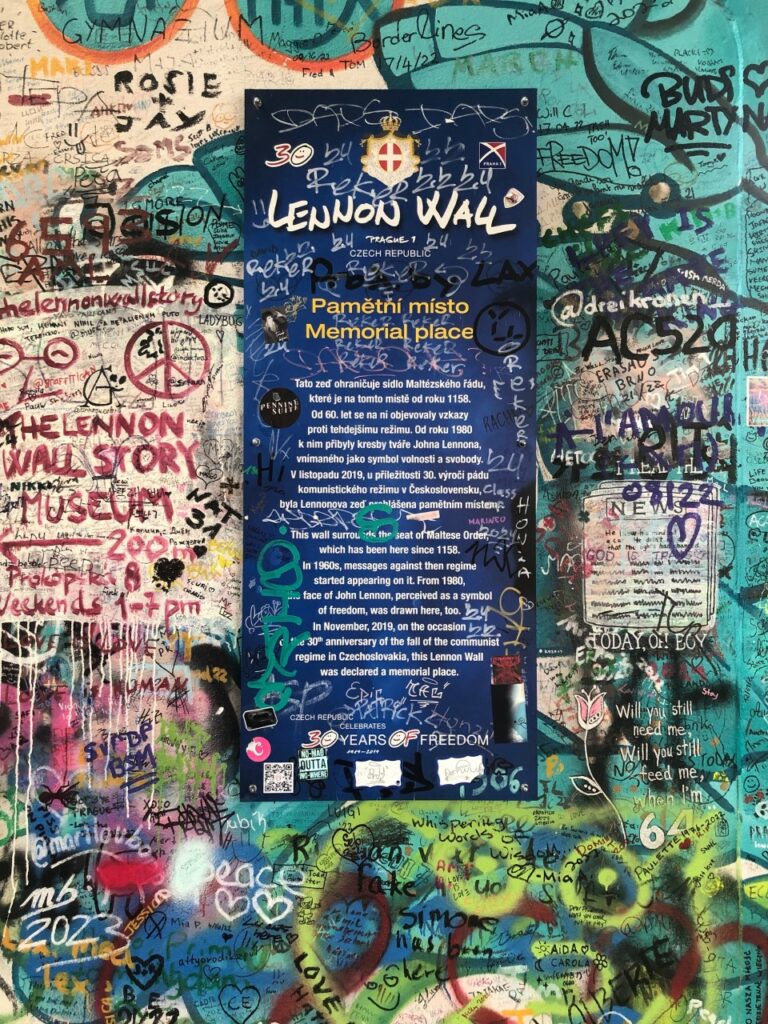

On my second day in the city, my daily exploration started with a visit to Malá Strana – also known as the Lesser Town – on the opposite side of Old Prague; a neighborhood founded in the Middle Ages and that was historically home for many ethnic German and Italian inhabitants of Prague. There, I admired a couple of beautiful churches, passed by the famous Lennon Wall – where locals used to creatively express their frustrations during the communistic period – and ended in Pétrin, the big green area of the city.

[The Lennon Wall, used as an anonymous complaints during the communist period / The remains of the old walls of the city in Pétrin]

Back to the Old Town, I crossed the iconic Charles Bridge, whose construction was initiated in 1357, to substitute a previous wooden structure, by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV. The statuary that adorns it is now mainly commissions from the Baroque period but additions have been made throughout the centuries. Even if the bridge survived the war structurally, it still suffered some damage during the conflict, since Nazis, as they were forcefully leaving the city by the end of the war, made a barricade to the Old Tower bridge gateway to slow the progression of opposing troops.

In the afternoon, I was lucky enough to join a group of local historians and architects from the University of Prague for a walk, as well as Mounir, a syrian architect that is finishing his PhD in the city and that sadly knowns firsthand the devastating and long lasting consequences war can have on cities, their heritage and people.

[Walking through the southern part of the city to check bombed buildings and its current state]

We walked through the southern neighborhoods – Nove Mesto -, to visited the area that was affected by one of the few bombings Prague witnessed during WWII, when Americans accidentally mistook Prague by Dresden. We passed by the worldly known futuristic Dancing House – a deconstructive building started in 1992 and designed by the star architect Frank Gehry – that was actually built in a plot that remained empty for a couple of decades due to this precise shelling. However, the most illustrative example of reconstruction in this part of town is the Emmaus Monastery, a gothic structure whose vaults were destroyed in the previously described event and that after a couple of reconstruction projects, the decision to add a new contemporary layer, representing its time, won in the 1960’s. Now, a Gothic foundation and a Modernistic tower co-exist in a somewhat harmonious way.

[The Dancing House / The Emmaus Monastery]

DAY 8: The Jewish Quarter

My third day in the city started with a really nice walk around town, with a local historian, Lukas, to observe newer projects that have been built in plots either destroyed during WWII or dismissed by the communist regime that followed, resulting in a very diverse approach to reconstruction and heritage preservation led after the conflict, varying, for example, depending on the location in the city or the typology of the building.

In the afternoon, I dedicated the majority of my time to the Old Jewish Ghetto of Prague, situated in the northern part of the city. A true city inside a city, even if the area is not very big considering the thousands that inhabited it before WWII, and that for many reasons throughout the centuries were forced to concentrate and keep to this part of town.

[The cemetery in the Jewish Quarter]

Nowadays, the neighborhood, completely included in the remaining urban system, hosts a significant minor number of jews, as many were deported and killed during the Nazi occupation of the country and many of those who survived decided not to come back. Nonetheless, the majority of the main structures that characterized the Josefov – also called like these to celebrate the Toleration Act, issued by Joseph II in 1781, granting the jews from Prague many rights – remain and have been carefully reconstructed and preserved. Among them, the synagogues – six in total – allow the visitors to have a glimpse of the rich history of the quarter, as some stand for centuries and date back to the medieval times, served as hubs for the sharing of fresh ideas or as a refuge for the jewish community during persecutions or pogroms.

[The Ceremonial Hall / The view of the cemetery]

I had the opportunity to visit the majority of them and was touched by how each one of them plays a role in understanding the neighborhood, as some remain religious buildings and others were turned into museums or memorials.

DAY 9: The Hill Over Prague

To end my stay, my last day in Bohemia’s capital was dedicated to the Prazsky Hrad, a fortified structure dating back to early medieval times; a place of coronation for the Czech rulers and of surveillance during war and occupation.

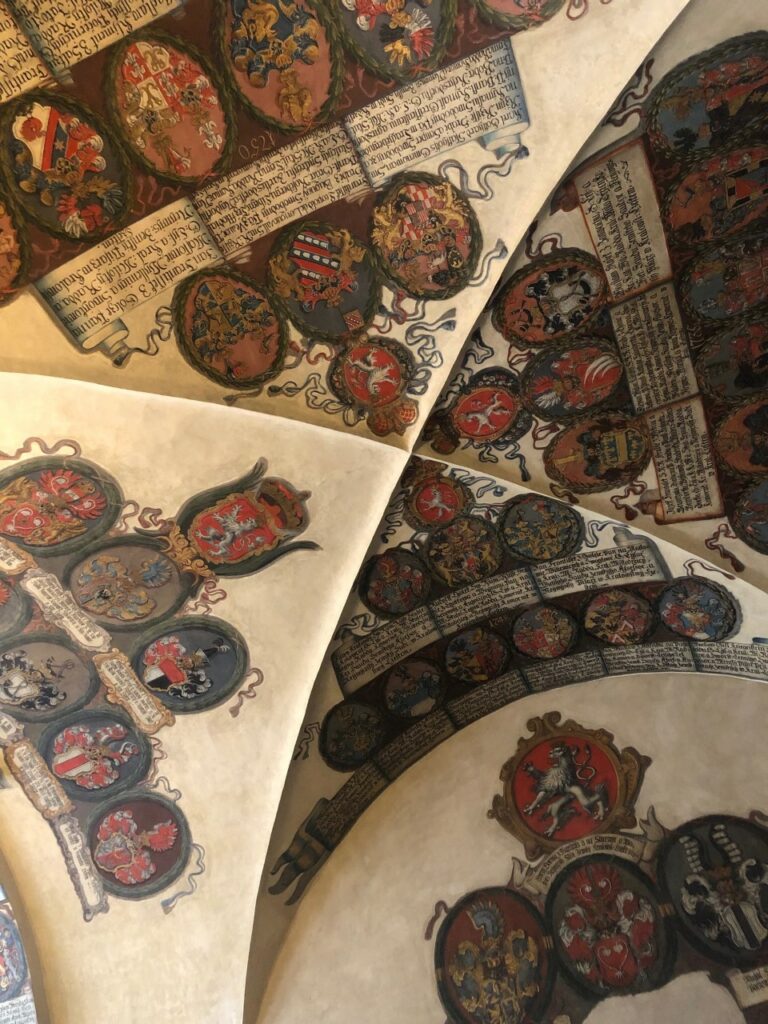

The castle started being built in the 9th century and since then has been a seat of power for the king of Bohemia, Holy Roman Emperors and Czech presidents. It has been reconstructed countless times after fires and wars and nowadays is a complex structure combining many different architecture styles, even if the predominant one is the Gothic.

[The view from the castle’s hill / The ceiling inside the oldest rooms of the castle / The main entrance of St. Vitus Cathedral]

Next to it, one can also visit St. Vitus Cathedral. The current structure, built upon an older rotunda by Wenceslaus – a king and patron saint – dates back to the 14th century. It is a marvelous Gothic structure, whose completion only ended in the 20th century. Original elements coexist harmoniously with newer ones: for example, a new decorated window by Alfons Mucha, a famous Art Nouveau artist.

To finish the walk around the hill and overlooking the city, the southern gardens of the castle were a later add-on. Its current state results from a project from the 1920’s, by the famous slovenian architect Josip Plecnik, for the first czechoslovakian president, T. G. Masaryk.

* HERITAGE HIGHLIGHTS *

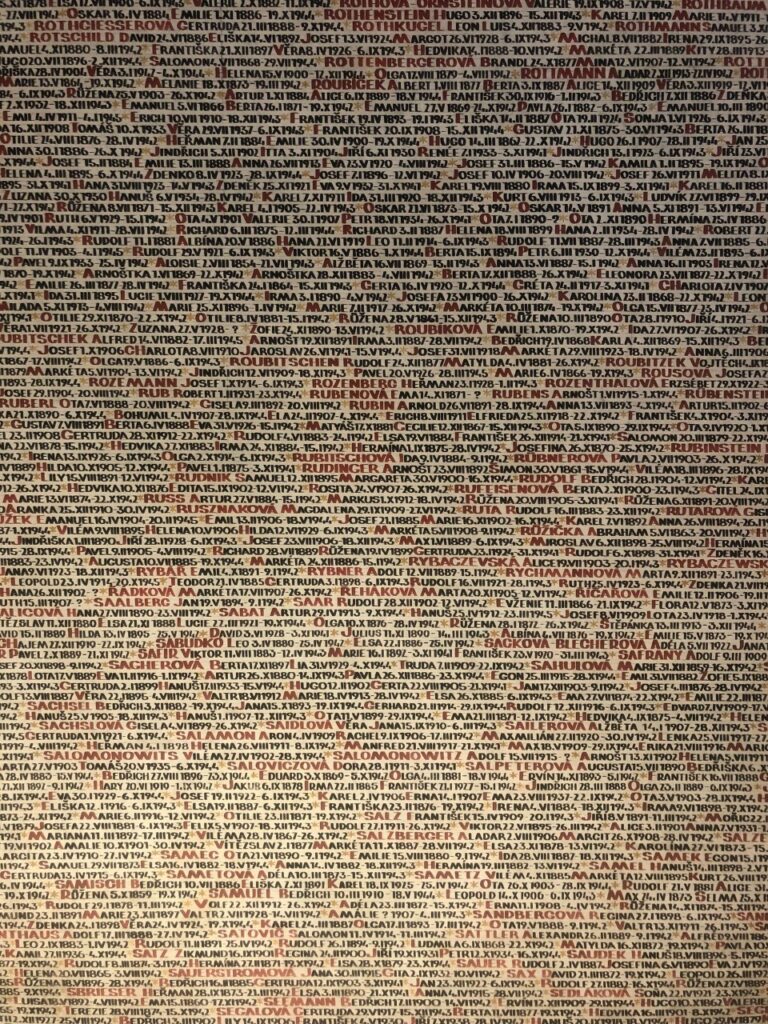

– Pinkas Synagogue –

Today a memorial, this synagogue speaks of the harsh chapter of history related to the Holocaust. Its walls are covered with all the names collected of deported Czech jews. Thousands died during WWII and in 1945, after the war, the jewish population of the city was reduced to less than a fourth. Apparently simple but impactful!

– Spanish Synagogue –

Before WWII, Prague had one of the biggest and liveliest jewish communities in Europe. The old ghetto had a couple of synagogues, being the last one to be built, the Spanish Synagogue, in the second half of the 19th century. Its Moorish Revival style is unique and speaks of the contemporary Jewish Enlightenment, which produced many famous books, marvelous music and works of art. During the historical Crystal Night, a pogrom in the prelude of WWII, in 1938, that purposefully destroyed many synagogues and jewish property in diverse cities around Europe, and it served as well as a shelter for the jews of Prague.

[One of the walls in Pinkas Synagogue, where the names of deported jews are organized by family name and city of origin / The interiors of the Spanish Synagogue]